Is Critical Thinking a Dying Art?

by Bryan Thomas Schmidt and Michael Wallace

Welcome to the age of soundbyte mentality, where memes have become a key means of pop culture communication and even the press have joined the politicians in not caring about the truth. Information overload, the advent of a 24 hour news cycle and the internet–information merging with entertainment–the failing of the school system with no child left behind (teaching to the test rather than educating on how to think), and social media (communication in 140 characters or less), these have all lead to memes becoming as prevalent as they have.

The trouble is memes, like soundbytes, are generalizations and half-truths at best, an easy way to box people up into quick, easy labels perhaps but misleading and no way to really define who they are. They are expedient and sometimes funny but when they touch on serious and controversial topics they can be harmful and hurtful and divisive, which is exactly why the press and political pundits love them so much. After all, these are people whose business thrives on conflict and drama, anything to get the emotions raging and people riled up. Except people are more complex than any soundbyte, unfortunately, and attempting to insist otherwise leads to no civility, no room for discussion and no room for critical thinking. Memes, like soundbytes, short circuit the thought process. They’re like outlines of a novel being used to define what the novel is, when the prose, in truth, brings so much more depth and complexity.

The trouble is memes, like soundbytes, are generalizations and half-truths at best, an easy way to box people up into quick, easy labels perhaps but misleading and no way to really define who they are. They are expedient and sometimes funny but when they touch on serious and controversial topics they can be harmful and hurtful and divisive, which is exactly why the press and political pundits love them so much. After all, these are people whose business thrives on conflict and drama, anything to get the emotions raging and people riled up. Except people are more complex than any soundbyte, unfortunately, and attempting to insist otherwise leads to no civility, no room for discussion and no room for critical thinking. Memes, like soundbytes, short circuit the thought process. They’re like outlines of a novel being used to define what the novel is, when the prose, in truth, brings so much more depth and complexity.

Are we raising future generations incapable of critical thinking? And are previous generations forgetting how to think critically themselves?

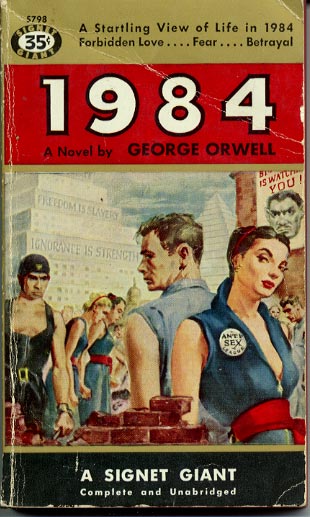

This is how we descend into a new techo-dark age, that is paradoxically driven by an over infusion of information that’s not be processed by people because they have lost that ability to make value judgments. This is a world in which a richness of technology and knowledge gets lost in the shuffle of our inability to access and apply it. Worse yet, perhaps it’s a world in which we no longer care. When nothing has any particular importance placed on it, everything becomes meaningless. Forget 1984 and Big Brother, forget Homeland Security and loss of privacy, if we allow an Orwellian society to take root—much like Hitler was elected into power—just because we’ve lost our ability to ask the very questions that might help us defend ourselves against such abuse of powers.

Science Fiction and Fantasy have long posited a dark future, but also often suggested that the key to avoiding such futures lies within ourselves. It starts with education—and that means being taught in a more classical sense. Study of philosophy, literature, and civics are essential for well-rounded understandings of our past as well as critical thinking in making good decisions for our future. More than ever, it’s important to ask the right questions. Not questions based on the assumptions that corporations, the government, media and politicians make for us, but deeper, moving beyond soundbytes and memes to the critical level that strikes at the heart of the issues.

We need to cultivate the ability to step outside ourselves and look at things from several varying perspectives. This is especially vital in an increasingly cross cultural world. Be the change you want to see in the world—become multidimensional—to paraphrase Gandhi. Create your own reality or risk having it created for you. If we continue to pride ourselves in being an enlightened society, we must rise to the occasion and be enlightened thinkers who continue blazing the trail for human advancement. The future is within each and every one of us and they choices we make collectively and individually. Those collective choices are the very backbone of what defines our culture and our vision for the future. Don’t let others make those decisions for you. Instead of following the nearest soundbyte or meme, think for yourself.

We can no longer afford to align ourselves with predefined groups or labels where the loudest voices wind up speaking for us even when we don’t agree with everything they have to say. Labeling is an expedient to dehumanization, not the enlightened way, which requires you to think beyond the label. Imagine what our future would look like without critical thinking? Imagine where we might be now? The enlightenment (US constitution being the pinnacle) the civil rights movement – equality of the sexes, the internet, free speech, freedom of religion—none of these would exist without critical thinking. Our constitution is the ultimate template in human advancement and freedom but its greatest strength lies in our ability to revise and adapt it.

Critical thinking is the primary key in unlocking human potential. When people don’t have the ability to question the status quo, nations like North Korea are allowed to exist, times like the dark ages can swallow echelons of time. Without it we’d be like robots restricted by Asimov’s three laws, incapable of violating basic programming or even questioning our actions based on the uniqueness of situations and circumstances, finding a perverse logic in that programming that is the cause of our own extinction. Then the lowest common denominator really will have won by taking away one of the greatest abilities that defines us as human beings.

Critical thinking is the primary key in unlocking human potential. When people don’t have the ability to question the status quo, nations like North Korea are allowed to exist, times like the dark ages can swallow echelons of time. Without it we’d be like robots restricted by Asimov’s three laws, incapable of violating basic programming or even questioning our actions based on the uniqueness of situations and circumstances, finding a perverse logic in that programming that is the cause of our own extinction. Then the lowest common denominator really will have won by taking away one of the greatest abilities that defines us as human beings.

The responsibility to change these alarming trends rests with each one of us. Educate yourself. Look for voices of objectivity. Question motives. Teach your children to question and think for themselves. The key to our future is to keep the art of critical thinking alive and well, to seek solutions together in spite of our differences, rather than each trying to ideologically conquer the other into perfect conformity. Only together can we reach our full potential as human beings. There’s no better time than the present to try.

Bryan Thomas Schmidt is the author of the space opera novels The Worker Prince, a Barnes & Noble Book Clubs Year’s Best SF Releases of 2011 Honorable Mention, and The Returning, the collection The North Star Serial, Part 1, and has several short stories featured in anthologies and magazines. He edited the anthology Space Battles: Full Throttle Space Tales #6 for Flying Pen Press, headlined by Mike Resnick. His children’s book 102 More Hilarious Dinosaur Jokes For Kids is forthcoming from Delabarre Publishing. He’s freelance edited a novels and nonfiction and also hosts Science Fiction and Fantasy Writer’s Chat every Wednesday at 9 pm EST on Twitter. A frequent contributor to Adventures In SF Publishing, Grasping For The Wind and SFSignal, he can be found online as @BryanThomasS on Twitter or via his website. Bryan is an affiliate member of the SFWA.

Michael Wallace is a musician, philosopher, and academician, engaged in the liberal and technical arts. check out his band ‘Flying Killer Robots’ on Facebook. www.facebook.com/pages/Flying-Killer-Robots/20358694661 He can be found on Twitter as @zebramax.

Thanks to Bryan and Michael for the thought provoking article; critical thinking is something which I feel very strongly about and I would like to respond to a few points in this article.

First, there are some assumptions which I disagree with and, this being an article written by Americans for an American audience on a fantastic American podcast, may cause some consternation.

My quarrel is with the reference to the US Constitution as the pinnacle of the Enlightenment. The Constitution is a magnificent document which enshrines the hopes and values of great men for the sake of creating a new nation – it is not the pinnacle of the Enlightenment though, as much as one of it’s many highlights. Just read some of Neal Stephenson’s books for a grand tour around some of the Enlightenment’s other highlights or simply go and see some of the architecture or read some of the works from the period. I don’t mean to denigrate the Constitution in any way, but it must be put in a wider context for critical comparisons and the bases of critical arguments to be made.

My other bone of contention (and I’ll admit “bone of contention” and “quarrel” are two ideas which are too strong to describe a feeling of good natured argument), is the nature of being overloaded with information. In the essay above, the key element in our troubles seems to be the teaching to tests, not the gift of learning to enquire critically; I have no argument with that part. The emphasis on humanities however, irritates me a bit. Those of us who tune in, or drop by the webpage here are all, by willful participation, lovers of writing or writers ourselves; this should not be an excuse to bias our attitude to fields like mathematics and science when considering critical thinking. Many of the greatest SF writers have been commited scientists and many great SF novels that challenge us have been, if not religiously scientific, meticulously thought out and meditated upon by intelligent, critical writers.

My final point is not an argument or a disagreement, but a different story. The story put forth above about a technological dark age is a striking one, a tale of disempowerment and decline in participation, of the cheapening of publci discourse and the occasional villification of the genuinely difficult/complex. We see aspects of this in all our daily lives, but there may be another story, another narrative at work.

As in the High Medieval, the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution and the Pre- and Post-War periods, we are not seeing the diminishment of critical thinking, but the reordering of value. Critical thinkers are both born and taught, people with enquiring dispositions and fine senses for logical arguments, aspects which can be honed through education. Perhaps in the same way captains of industry replaced captains of regiments, that scholars went on (and still go on) to become ministers and congressmen, we are waiting for our new intellectual agitators to arise.

We have delighted for ten or twenty years in the development of a global internet, mass media, a networked economy and done so in the fashion of gloriously captivated children at play. As we head into the next twenty years we will grow and mature, and people will announce themselves as the new brand of critical thinkers. They will replace the academics and intellectual leaders of the telephone age and become the flag bearers of the mobile media generation, settling into new patterns of value and discussion, but using the ancient statutes of critical thinking (unconsciously or not) to make decisions about the education and welfare of the generation to come.

Now, I understand the last few paragraphs of my response are a bit poetic and definitely rhetorical (sorry to the philosophers out there), but while it may be more relevant or less relevant than the dark age example above, I feel it may be more hopeful.

Thanks for a great article which has provoked such a wordy and long-winded response from me! 🙂

Hi James

Thank you for your contribution to this discussion, you’ve brought up some very salient and thought provoking points. This is what critical thinking is all about.

I, too, thought perhaps our essay was a bit too Amerocentric, and it was toned down from its original form, but you write about what you know. A lot of what prompted this article are recent trends in American political, educational, and interweb circles.

Bryan and I share some ideas, and are widely divergent on others, so I’m speaking only for myself here. Bryan is more than capable of speaking for himself.

The reason I would place the US Constitution as the philosophical capstone of the Enlightenment is simply because of the influence it’s had as principal put into action, changing the course of humanity. There’s also the French Constitution, of course – several other foundational documents have been directly copied or closely modeled both these documents. I actually view the US Constitution as the highest expression of European idealism. In no way is that to suggest America is better than any other country, but it does suggest America has had a greater reach and influence than any other nation, particularly in the last twenty years (for good or ill). That in no way was meant to denigrate any other nation’s achievements in this realm.

You also said ” The emphasis on humanities however, irritates me a bit.” Perhaps this could use some context and clarification. Again, in the US we are seeing the humanities – art, literature, civics, history, muisc, et al, being diminished (dumbed down) or eliminated altogether in the public school curriculum. I personally was suggesting a well rounded, inclusive educational program – a balancing of the arts and and sciences. Frankly, we need to teach science and mathematics much more aggressively as well. If an emphasis was implied, it was not intended but borne out of the diminishment of these disciplines in the US and the need for a restoration to achieve the aforementioned balance.

I agree that an Orwellian future is not a certainty, although there are, as you mentioned “aspects of this in all our daily lives”. Much of good, classic science fiction (including 1984 and Frankenstein) serves as a warning – as does this essay. Critical thinking will be the most critical tool in fighting the darkest version of the future … I am also hopeful and do believe that our humanity can someday work in harmony with our technology for the advancement of our species … but we all have to be active participants to achieve this parity. Thanks for your insights!

I’m going to let Mike answer for both of us because I like his response so much. It’s hard to get nuances for every contingency in pieces like this. We were generally thinking of an American audience, so please keep that in context. The discussions which led to the post had to do with the proliferation of memes and soundbytes in American culture more than anything else, although certainly there are always wider trends. Thanks for your thoughtful comments.

Bryan & Michael,

Thank you for writing this article. The meme, the soundbyte, the 24 hour news cycle, and the generic labeling that is so prevalent in our culture does not allow time for the critical thinker to think and reason a response but promotes the visceral, the emotional, and the spilt second reactions. This prevalence gives the stage to the loudest voice with the k

Okay my fat fingers caused me to post before I was finished, so to finish…

This prevalence gives the stage to the loudest voice with the most divisive, polarizing, and extreme stance whilst regulating the reasoned, logical, and thoughtful responses to the hinterland on the public arena.

Thanks again for writing this essay.

I particularly liked your comparison to an unthinking public to robots adhering to Asimov’s Laws. In the USA, these laws seem to be: 1) If they’re sexy people near it, buy it. 2) If it’ll get the fat cats out of Washington, vote it into Washington. 3) If it tastes good, eat it until you puke.

Without the iron guard of critical thinking, we are slaves to advertisements. Flip on the TV and be bombarded by widescreen hamburgers dripping with savory lust or beer sweating with popularity. As a result, obesity has become an epidemic, and the average person seems able to do more than to self-flagellate themselves after binges with fad diets that sets their weight on a roller coaster.

It’s definitely all about manipulation and most of it used for motives other than common good sadly, AE.

Essentially we become slaves to governmental, political, and corporate control once critical thinking exits the picture. I stopped watching commercial television years ago because I found the constant barrage of adverts not only irritating, but insulting – not to mention, painting a portrait of our culture which was extremely unflattering. 😉

I don’t quite agree with the premise of the article. It’s not like memes are a new phenomenon. They are how culture is spread. Deep, complex, controversial ideas can be packed into pithy packages.

And it’s not modern communications technology, the internet, and social media that are eroding critical thinking. The authors do hit upon the true culprits, however: the government-corporate-media establishment with their public schools designed after the Bismarkian model (to regiment and indoctrinate students into being good, ignorant, docile, obedient citizens), their propaganda, their bread and circuses, and their infotainment soundbyte “news.” A general populace capable of critical thinking is not conducive toward keeping our plutocratic rulers in power.

“They are expedient and sometimes funny but when they touch on serious and controversial topics they can be harmful and hurtful and divisive, which is exactly why the press and political pundits love them so much.”

The culprit is not the memes themselves. I would venture to suggest that part of the problem here is the failure to think critically about these memes. Some memes are we are encouraged by the establishment to hold as sacred, others are a threat to the establishment. In either case, instead of thinking critically about these memes, people tend to respond with emotional, knee-jerk reactions. We see this in response to politically unpopular ideas, be they competing memes or challenges to the sacred memes. People gang up to denounce the offender with much venom and bile and ridicule, angrily calling for the person to apologize and retract the offending statement/meme and be fired or resign. The masses — or at least certain well-organised special interest groups — rise up to squash independent, critical thinking and marginalize those who engage in it.

To get even more heretical, I do not think the Enlightenment and the US Constitution should be held up so uncritically as the pinnacles of human achievement. There were many things very wrong with both that we would do well to jettison. To scratch the surface: in philosophy, there is the rationalist-empiricist dichotomy, the fabrication of the is-ought gap, and the rejection in ethics of the classical focus on the well-being and perfection of the individual in favor of the maintenance of social order through a focus on social duties.

When it comes to the US Constitution, I’ll go out on a limb and commit the ultimate heresy. I must echo the great 19th century jurist and abolitionist Lysander Spooner, writing after the Civil War:

“But whether the Constitution really be one thing, or another, this much is certain – that it has either authorized such a government as we have had, or has been powerless to prevent it. In either case, it is unfit to exist.”

Let the stoning commence. 🙂

“The culprit is not the memes themselves.”

Or, to be more precise, the problem is not memes as such, but people who spread or squash them and the institutions that undermine critical thinking. To be sure, some memes are “designed” to discourage critical thinking, and I would number among them the sacred memes of the establishment.

As a teacher and a scholar, I want to applaud the authors’ enthusiasm for critical thinking, but as a reader I find myself deeply confused about most of the fine points of the message. Taking the authors seriously, I want to demonstrate a little critical thinking in response to their article.

I take the main points of argument to be that (a) communicative carelessness is a new problem, or at least the form and scale of the problem is new; (b) a certain sort of education which they call “classical” is needed to combat the problem; and (c) that type of education will produce (or is more likely to produce) people who ask questions.

I suppose that’s a correct picture, as summaries go. In making these points, I think the authors employ some strikingly false notions that bring the whole picture into question. The first is the much lamented “failure of the school system.” Well, failure according to what? When most politicians talk about this supposed grand failure, they’re referring to the PISA global rankings, which are based on test scores. You can find a Washington Post article (12/9/2010) about a study by USC professor Stephen Krashen that shows *when you control for poverty,* the U.S. is by far the highest scoring nation in the world. Finland, which is usually top in the world, has a PISA score that is almost 20 points lower than ours. The problem is that the U.S. educates many, many more children living in poverty than any other OECD country taking part in the PISA rankings. Poverty, not quality of teachers and not quality of textbooks, but poverty is the primary indicator for student success.

That’s well and good, but you might be thinking about your own miserable high school experience and wondering how in the world we could be the best in the nation. I’ve been both a high school student and a (reluctant) high school teacher, so I can tell you what you’re missing and it’s this: when you were in high school you were a hormonal idiot. Your teachers, most of them, were perfectly intelligent, capable, albeit stressed out and overworked (you have no idea) professionals. You were a terrible student. It’s that simple. During my first year of teaching, as I was failing to get my students to appreciate the history of knowledge through a study of literature, it hit me like a ton of bricks just what terrible students most people are (and I was at that age). Believe me, however you think you remember your high school teachers, in most cases the problem was you, not them.

But I also want to make another point here, which is that teaching to the test isn’t a problem…when teachers have the freedom to design the tests to fit their classes. If I could design my own end of the year exams, then my students would be taking an essay exam about the development of the concept of knowledge from Plato’s Cave through Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, and you bet your you-know-what it would be one hell of a test. I would “teach to it” all year long and my students would be all the smarter for it. So teaching to the test isn’t the problem. In fact, I would go so far as to say that teaching to the brainless NCLB standardized exams isn’t a problem (for teachers). We simply have to do it, or we’re fired. It’s a problem for the students, and it’s a problem created by politicians who know jack about teaching.

This is running long, so I’ll move on to a bigger problem. It’s this idea that information overload is leading to a loss of ability to make value judgments. I think this presumes something strange about how we learn to make value judgments, as if we are presented with certain clear propositions about what is good and what bad. So, if there are too many propositions or if the propositions are confused, then it is no longer clear what is good and what bad and we run into a sort of bland moral relativism. I don’t think this is correct, because it has cause and effect backwards. The reason we’ve become so enamored of bits of information is because we *first* stopped believing that some things were objectively good and some things objectively bad. If we believed, as did Medieval people, that there were truly trivial things that didn’t merit our attention and truly important things that did, then we wouldn’t have gone gaga over mass media in the first place. The failure was first a failure of moral perspective, which resulted in a failure of moral education, and now results in the reign of the trivial.

Can classical education help? I have my doubts (and I have a Classics degree). Hitler’s Germany was the most thoroughly classically educated culture in the history of the modern era, and look what they did.

It seems to me the misunderstanding here is premised upon your idea that asking questions (which a classical education facilitates) is somehow an obstacle to the abuses of power. It isn’t. Historically, it hasn’t been. The only surefire obstacle to the abuse of power is to teach children to love what is good and despise what is evil. That’s right. The only way to avoid the abuse of power is to raise children to believe in certain moral absolutes that are crucial to the functioning of a democracy. That is how you provide an *objective* foundation, one not subject to the dangers of whim or the vices of untutored personal preference.

I know you may not agree. You say something like, “don’t let others make decisions for you.” But what if someone has expertise that you lack? Wouldn’t it be prudent to defer to their knowledge? This is the conversation we have to recover in the West, a conversation about right versus wrong, of good authority versus bad, and of a robust moral education versus the depressingly superficial moral relativism of the present. You close by saying we have to seek solutions despite our differences. What about situations in which the only possibility is an impasse (think abortion, death penalty, war, gay rights, taxation)? In those situations, we need a common moral education so that we can live with each other in the face of permanent disagreement.